‘Billy Lynn’s Long’ Walk Away From Cinema (Movie Review)

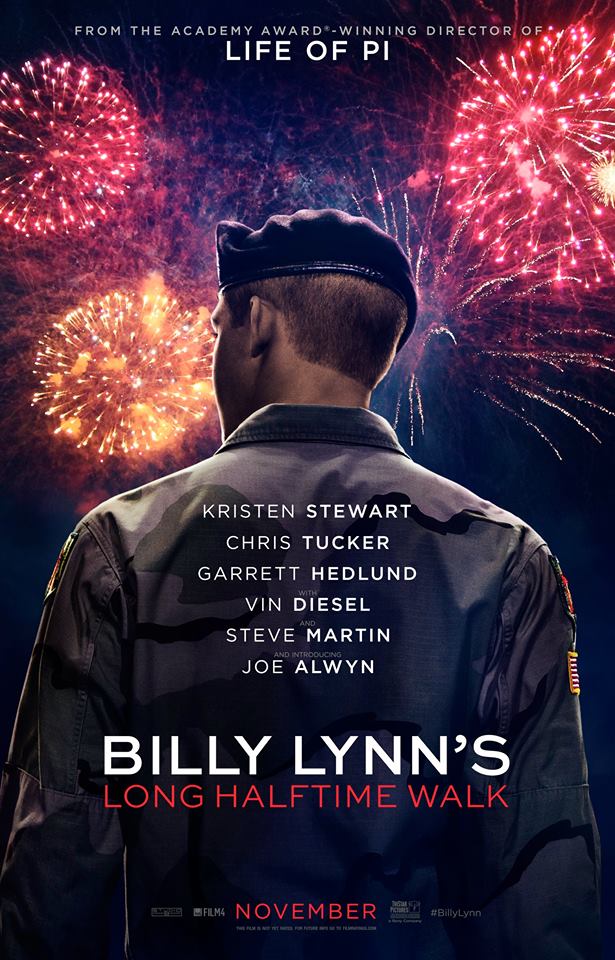

In addition to being a talented journeyman director, 2-time Oscar winner Ang Lee has shown a profundity for technical ambition in his films. 2003’s Hulk, flawed as it, could still be considered one of the more ambitiously made superhero films of the modern age. Life of Pi is one of the few films in this post-Avatar world to properly utilize 3D as more than just a monetary-based gimmick. Now we have Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, a dramatic satire focused on a young Army specialist and how he deals with newfound fame back in 2004 America, following a heroic act while fighting in Iraq. For this, Lee went with the whole shebang, shooting at 120 frames per second in 3D at 4K HD resolution. That is wild just to think about, but the results are a film that is not only overly familiar from a story standpoint, but lacks the essence of what makes me appreciate cinema.

In addition to being a talented journeyman director, 2-time Oscar winner Ang Lee has shown a profundity for technical ambition in his films. 2003’s Hulk, flawed as it, could still be considered one of the more ambitiously made superhero films of the modern age. Life of Pi is one of the few films in this post-Avatar world to properly utilize 3D as more than just a monetary-based gimmick. Now we have Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, a dramatic satire focused on a young Army specialist and how he deals with newfound fame back in 2004 America, following a heroic act while fighting in Iraq. For this, Lee went with the whole shebang, shooting at 120 frames per second in 3D at 4K HD resolution. That is wild just to think about, but the results are a film that is not only overly familiar from a story standpoint, but lacks the essence of what makes me appreciate cinema.

Now this shouldn’t be a review about what is and isn’t cinema and far be it from me to tell someone like Lee what movies are, but Billy Lynn puts things into an interesting position. Just a couple weeks ago I saw Doctor Strange and liked it well enough; particularly because it showed some cinematic ambition. Now others have claimed this is the first Marvel Studios movie to feel like an actual film. I think that undersells what those films accomplish, but matching something like Strange up to Billy Lynn and I can see a better point being made.

The idea here was to show this story in a way that feels intensely real, given the framing of these characters and the clarity in which we see them act. Just as with The Hobbit films though, I feel like this is an attempt that ultimately backfires. Credit to Peter Jackson, at least The Hobbit films embraced fantasy and used its 48 fps presentation to allow people to revel in the visual effects (even if the practical production design felt compromised). With Billy Lynn, the film presents real world scenarios, with the shooting style giving an audience the look of well-composed rehearsal footage.

At 110 minutes (with credits), Billy Lynn is thankfully not overlong, but only 2 of those minutes actually feel important to why Lee would choose to shoot a film this way. A sequence involving Billy Lynn (Joe Alwyn) fighting off an Iraqi soldier allows for a look at what one does to take a life. It’s not reality, but I see what the film is trying to do. If anything, the best method may have been presenting the film in a way where only the action and the actual halftime show were broadcast in 120 fps and the rest of the film was shown traditionally.

Now clearly a lot of my thoughts have been put into the shooting style. This may have mattered little were the story to present more than just an overly familiar drama about a man questioning his heroism in the face of many outside that life, with their own naïve opinions. The film tells the story of Billy Lynn, a member of Bravo Company squad, who has returned to the US with his comrades to go on a promotional tour, following a celebrated heroic act that was caught on camera. In particular, this story focuses on the end of that tour in Dallas, where the men go through a day that will involve them being on stage at a Thanksgiving home game during the halftime show. We also see flashbacks to Billy’s big moment.

To its credit, Billy Lynn keeps its focus on Billy and holds onto the idea that this 19-year old boy chooses to only comprehend what he has gone through, rather than present ideas wrapped up in politics. Thanks to other narrative choices and a solid performance by Garrett Hedlund as the leader of Bravo Company, the film even digs at the idea of overloading on American jingoism, in favor of keeping the beating hearts of these men as the thing to care most about. It is ultimately what helps us have an understanding why Steve Martin’s millionaire Norm Oglesby character is a villain to watch out for.

When the film does cut to the Iraq flashbacks, there is a level of excitement to be had in seeing action playout, but it only amounts to so much. The effort is there to explore Billy’s PTSD, but it’s not the first film to do so and others have had stronger performances (all due respect to Alwyn) to bolster these types of stories. That’s a shame too, as Kristen Stewart plays Billy’s older, more opinionated sister, but the script has little for her to do, other than present the idea of abandoning the Army all together.

Most of the characters have little to offer. Chris Tucker is game to play against type as an agent trying to work out a movie deal, which this film has little insight on as far as what kind of work actually happens in that sort of scenario. Vin Diesel plays Billy’s former C.O. and provides the sort of encouragement you’d want, with little shading. The best stuff may just be the comradery between the soldiers and Hedlund’s sarcasm blended with a no-nonsense attitude.

There is some unneeded manufactured drama put forward in an attempt to provide Billy reasons to flashback to his experiences, but the film misses its marks when it comes time to making itself a more engaging affair. One would think the shooting style (and many close-ups) could make the experience feel more intimate, but it doesn’t. With this realistic angle, there is no chance for the film to get softened by a traditional format. Since we are watching movie actors in an experience that looks akin to theater, there is something off about the way the drama unfolds altogether. The amount of clarity doesn’t do any favors for the overacting background extras either.

While the focus has been on technique, that doesn’t mean it is an excuse to disregard what else is going on in the film. Billy Lynn is obviously an ambitious production, but coupling the experience (which will be rare for a majority of audiences to actually see) with a familiar story does not make for a rewarding experience. Instead, I continue to find myself ill at ease with the idea of seeing more films that utilize a higher frame rate. Perhaps James Cameron will be the one to finally make this a worthwhile venture. Lee, for all the good that he can bring to film, seems to be working against cinema with his actions here, and whatever else went on had only so much to offer, regardless of it.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()