Little Women Make A Big Impact (Movie Review)

The best film of the holiday season has arrived. Writer/Director Greta Gerwig follows up her acclaimed debut, Ladybird, with nary a sophomore slump. Time will tell, but Little Women may be better than her 2017 Best Picture nominee. Ladybird made Gerwig the fifth woman ever to receive a Best Director nom by The Academy Of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Could Little Women lead to winning Oscar gold? Whatever happens, the film closes out the decade with class, wit, and a few tears.

–

Louisa May-Alcott’s beloved novel has had more than ten iterations on the small/big screen. Katherine Hepburn and Winona Ryder, among many others, have played the Jo March of their generation. For this latest adaptation, Gerwig has assembled an incredible cast that includes Saoirse Ronan, Meryl Streep, Florence Pugh, Timothée Chalamet, and Emma Watson. In making this film, Gerwig succeeds in both staying faithful to the source material and updating it for the modern era.

The book was initially published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869. It was written as a somewhat autobiographical tale of Alcott’s life growing up with her three sisters in Concord, Massachusetts. For their time, the March girls lived a (mostly) privileged life. Their only real concern was the safety of their father, who was off at war. As a result, the four young women were able to hone their talents: writing, acting, painting, and music. 2019’s Little Women is very much the same story with 21st-century sensibilities and an effective structural re-working.

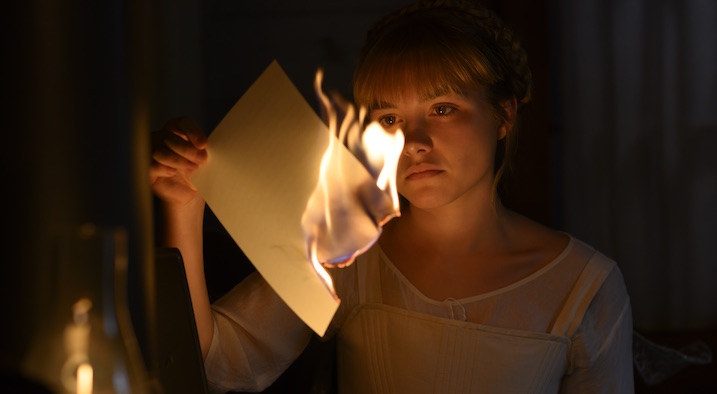

Gerwig’s version wisely focuses on the creative endeavors of Jo (Ronan), the main character, and her desire to write. The opening scene highlights a nervous but confident Jo having a meeting with a would-be publisher (the great Tracy Letts) of one of her short stories. Very quickly, it is mansplained to her how if her story has a female in the lead, the heroine must be married by the end. Right off the bat, Ronan imbues Jo as a combination of the right amount of fortitude yet inexperience in life. She’s a woman ahead of her time but by no means flawless.

The terrific hook in Gerwig’s script is how the structure of the story is literally concerned with time: how it forms and unravels. Time shifts back and forth between two periods. We see the March girls when they were growing up in their home, and years later, as adults, now separated, trying to make their way in America and Europe.

The structure presents these women as figuratively unstuck in time. It’s a simple device to mix up the narrative by keeping viewers just a little off by trying to figure out what is past and what is present. Additionally, this design brings up concerns of gender inequalities of the past, which reflects on how it’s still around today.

Many great filmmakers have found their own way of using time as much more than just a gimmick (Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction and Nolan’s Memento come to mind). Gerwig succeeds as well. Along the way, she has plenty of observations on class and age as well as gender. All of it is made more vital by the use of the script’s time shifts.

The cast is nearly perfect. The Ronan, as mentioned earlier, was a kind of Gerwig surrogate in Ladybird. In Little Women, she delivers a similar amount of weight and fussy humor to Jo, the de facto leader of the sisters.

However, Florence Pugh is the film’s real MVP as wannabe painter and successful troublemaker Amy. Like Jennifer Lawrence when she was first breaking out, Pugh (also seen in this year’s Midsommar and Fighting With My Family) has an incredibly strong onscreen presence matched by her smart choices. Though the early moments as Amy stretches her age believability (I think she’s supposed to be 12), Pugh (who is 23) demonstrates that casting a younger performer for those scenes wouldn’t have worked as well in the bigger picture. Seeing Pugh in the older sections where she’s become more resigned at her station in life pays off.

Moreover, when you have a supporting cast placing Pugh alongside Meryl Streep as a stuffy, strong-willed matriarch, Laura Dern as the most supportive mom ever, and Timothée Chalamet as the best guy to grow up with, it could be near impossible for a relative newcomer to make her mark. And yet, she does.

Eliza Scanlen and Emma Watson are the other half of the March sisters. As anyone who has read the book or seen the (quite good) 1994-version, starring Ryder and Kirsten Dunst, knows, Beth (Scanlen) is the sister who loves music and has health issues that may be a cause for concern. Conversely, Meg (Watson) is the one who dreams of being an actress and, unlike her progressive sister Jo, just wants to settle down with a husband.

I haven’t seen a lot of Scanlen’s previous work (she’s best known for the HBO limited series Sharp Objects), but she performs the part well. Watson, on the other hand, is still kinda just Watson. If there’s a weak link to the cast, it’s the former Hogwart’s alum. As Pugh impresses by making those great choices, whether with a line reading or the way she can fumble about on a not-so-safe frozen lake, Watson is less impressive. No one in the film is mediocre, but she doesn’t imbue Meg with much by way of personality (for the record, I really liked Watson in The Perks of Being A Wallflower).

Still, if it isn’t apparent by now, I loved Little Women. This is the rare kind of awards season film that resonates yet never feels pretentious. It’s because of Gerwig’s loose but strong directorial decisions and often hilarious yet tender script. The lush photography by the fantastic Yorick Le Saux (Personal Shopper) is transporting while the costumes by Jacqueline Durran (Atonement) make a period from over a century ago feel alive. This is a near-perfect kind of holiday film. See it.